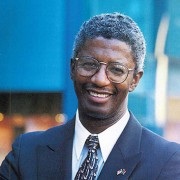

Millard Arnold Moves In

Ron Brown has placed his point-man in southern Africa. It’s an ambitious move to help Africa to get up and go for it Neil Lurssen surveys the prospects.

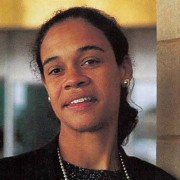

More than three years· ago when the South African transition was on the cards, but by no means a certainty, he wrote a paper for Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies in which he argued that one of the reasons for post-independence Africa’s decline was that no country or region on the continent had sufficient economic strength to serve as a catalyst. With the emergence of southern Africa free of the shackles of war and apartheid, Africa would finally have an engine for both it so desperately needed, he said. In his review of the region’s resources, he noted that, unlike any other region of sub-Saharan Africa, the countries in the south were remarkably compatible in their judicial, financial and institutional infrastructures. Millard W Arnold, Jr., the first United States minister-counsellor ever to be sent to South Africa for the sole purpose of promoting trade and commerce, is clearly one of those American Afro-optimists challenging the many Afro-pessimists in the United States who look across the South Atlantic and see mostly doom and gloom. The optimists say give Africans a fair chance and they will achieve great things. The pessimists look at the mess created by nature, history, the colonial powers and inept politicians and see little hope. From his office in Johannesburg, Arnold’s mission is to develop and manage American commercial activities in what is designated by the US Department of Commerce as one of the world’s 10 big emerging markets. In effect, he is there to help the disadvantaged people of southern Africa to get a fair chance to reach their potential in a democratic, post-apartheid market economy – while promoting trade opportunities that can create jobs for Americans. The theme is black economic empowerment in southern Africa and new markets for American exports, with an emphasis on those produced by black American companies. Certainly, from the American perspective, there are good reasons to be pessimistic about Africa, starting with the nightly television news broadcasts with their grim scenes from Rwanda, Somalia and other hell-holes, and ending with familiar accounts of continent-wide overpopulation, economic decay and political corruption. But there are good reasons to be optimistic and the Clinton Administration’s policy planners hope the Afro-optimists will use their talents and energies to counter the gloomy prognoses of the pessimists. One of the Administration’s strategies in this context is to foster an African constituency in the United States. The South African transition has given the Afro-optimists exactly what they need to push their cause. News coverage of the long lines of voters waiting in the sun to take part in the new democracy and the colorful inauguration of President Nelson Mandela sparked an American emotional high – especially among African Americans – which Clinton planners hope will help them boost South Africa into the role of the catalyst that will turn Africa around. Arnold, a 47-year-old Washington author and lawyer whose resume includes 19 years of public and private international law practice, much of it involving Africa, was an optimist long before Nelson Mandela took his presidential oath of office.

With excellent ports, the makings of a substantial transport and communications network, with Africa’s most sophisticated financial institutions and with most of the mineral, oil and agricultural potential barely tapped, prospects seemed pretty good, Arnold suggested. In his new job, Arnold – who served in the Carter Administration as a deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs – has an opportunity to help bring nearer to reality his vision of the region exploiting its resources properly for the benefit of everyone. His area of responsibility includes South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Mozambique, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland, Angola, Zambia and Malawi. He will serve as principal advisor to US Commerce Secretary Ron Brown and to the American ambassadors in the countries under his jurisdiction.

Millard Arnold’s appointment ties in with the new American foreign policy doctrine of preventive diplomacy which is evolving, not without difficulties and stubbed toes, in the place of Cold War strategies where nations sometimes qualified for partnership even if they were scurrilous dictatorships but were considered useful in the anti-Soviet effort. The new doctrine aims to help countries deal with short and long term problems so that US foreign aid, never popular among American taxpayers, can be used for development rather than emergency relief during crises when the hungry have to be fed and US soldiers often have to keep the peace. Thus, Clinton planners judge a strong and stable South Africa, with economic benefits spreading out over the region, to be very much in the American national interest now and for the future. They want South Africa to grow. President Mandela’s speech to the Organization of African Unity in Tunis in which he urged Africans to deal with their own problems was much applauded in Washington. But the Americans recognize that Mandela must have economic clout to back up his moral leadership. At the time of writing, Arnold was still drawing up a game plan for his new job. But his boss, Ron Brown, has already set guidelines. It is clear that Arnold will have an open telephone line to Brown’s office.

The Johannesburg posting seems to have a very special meaning for Brown – the first African American to be appointed US Secretary of Commerce. In an emotional speech earlier this year to students at Howard University in Washington DC., Brown said this of himself: “My ancestors, came from Africa. Some 200 years ago they were led in chains on to a slave ship… I feel a special connection to these events. A man whose ancestors were brought to America by the slave trade now shapes American trade policy as Secretary of Commerce. So much has changed; too much remains the same.” Brown went on to relate the changes in South Africa, with a warning that matters could not remain the same in terms of black economic exclusion there. In several speeches, Brown has described the US eagerness to help bring all South Africans into the economic system as managers, consumers, skilled workers and entrepreneurs. “This is the area where the US can make its greatest contribution,” he said. “Just as the economic pressures of sanctions and divestment helped end apartheid, economic assistance and private sector investment and trade can help encourage the healing process…. “It will be the private sector that drives the economic recovery in South Africa. Only substantial private investment domestic and foreign – can fuel the economic growth needed to provide the jobs, housing, education and human services to those so long excluded by apartheid.” Millard Arnold’s job is to try to tum those words into facts. In Washington, Arnold told the US-SA Business Council that he envisaged a central co-ordinating point for American firms doing business with South Africa to bring together all the numerous policies and programmes introduced by the Clinton Administration. His job, he said, was to promote:

- American economic engagement in South Africa and the region;

- The interests of American companies;

- South Africa and the region as venues for direct investment by Americans; and

- The economic empowerment of black South Africans in conjunction with American businesses with an emphasis on – but not exclusively – business owned by African-Americans.

Clearly, Arnold will be an influential figure in the bilateral relationship between Washington and Pretoria. Commercial and trade matters will be high priorities with tax and tariff treaties and trade strategies getting much attention. But the bottom line for his success or failure will be whether American investors feel their money will be safe and profitable in South Africa. And only South Africans will be able to control that.

Neil Lurssen is Washington correspondent at South Africa Magazine

South Africa, The Journal of Trade, Industry and Investment

Publisher, David Altman

Writer, Neil Lurssen