Dem Bones

South Africa has underground treasures which outshine its gold and diamonds. Anita Allen shows how they can be explored through the fascinating world of archaeo-tourism.

It is 70 years since the February 7, 1925 edition of Nature, the journal of the Royal Society, published an article by a little known professor of anatomy at a fledgling medical school in a rough and ready gold mining town called Johannesburg. The article shook the world with its claim that Africa was the cradle of humankind. Professor Raymond Dart retrieved the rock containing a child’s fossil skull from a limestone quarry near Taung in the arid Kalahari region of South Africa in 1924. At the time, the widely held view was that modem man descended from ancestors in Asia.

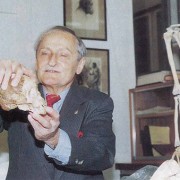

Dart realised that the Taung skull was unlike anything previously discovered. It was neither man nor ape, but something in between which had walked upright a real missing link. Australopithecus africanus, as Dart called it, opened a new chapter in the search of man’s origins, but it also brought an avalanche of criticism. His claim that the Taung skull represented a new species in the line of human descent was considered heretical. His view that it confirmed Charles Darwin’s 1859 prediction of the African origins of man was greeted with shock and derision. Echoes of this are still heard from time to time. For 25 years Dart was virtually alone in upholding his views, but by the early 1950s, due to the uncovering of the Piltdown hoax, the human-like status of Australopithecus was established. In the next 30 years it became universally accepted as a member of the hominids, distinct from the pongids or apes, and recognised as one of the earliest primates to embark on the line of humanising changes that spawned modern man. As many more African hominid fossils were unearthed, evidence accumulated that they were more primitive and more ancient than the oldest fossils found in Asia. “Whichever hallmarks of hominization we may regard as signifying the Garden of Eden, the record of the rocks points unerringly to an African locale, long before the corresponding features were found anywhere else in the world,” says Professor Phillip Tobias, South Africa’s most respected palaeo-anthro-pologist and Dart’s successor at the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School. “Africa, as the greatest piece of real estate straddling the equator, was ideally placed to become the crucible for the greatest human experiment.” Men like Dart and Tobias belong to a select band who changed the way we think about ourselves, but beyond their fellow palaeo-anthropologists they are as little known to the outside world as is South Africa’s rich fossil heritage.

However, this is changing. South Africa’s international acceptability following its transition from apartheid to democracy is helping to position the country as a premier destination for archaeo-tourists. About 50 per cent of all early hominid fossils originate in South Africa. Much of the work is concentrated among scientists attached to, or graduates of, the faculty established by Dart and expanded under Tobias. Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand, or simply Wits, controls the world’s single richest hominid fossil site, Sterkfontein – a mere 45 minutes’ drive from Johannesburg. Sterkfontein lies in an ancient valley thick with dolomitic caves. Seven other sites in the area are being excavated by scientists of Wits’s Palaeo-anthropology Research Unit (PARU). All the sites have yielded hominid fossils. Work at Sterkfontein began in 1936 under another world renowned paleoanthropologist, Dr Robert Broom. His most famous find was the almost complete skull of what has come to be known affectionately as Mrs PIes, a name derived from what Broom at first judged was a new genus and species, Plesianthropus transvaalensis. The fossil has since been recognised as the same species as the Taung child, Australopithecus africanus. Excavations at Sterkfontein have yielded over 600 000 fossils, the oldest dating back 3.5 million years. Among these are no less than 700 hominid fossils, making it the richest source of early hominid fossils on the planet. Finds include the remains of the earliest member of humankind’s genus, the first tool user, Homo habilis, which means handy man.

In October two astronauts from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration notched up a first when they stepped out of the Space Age into the Stone Age at Sterkfontein. Winston Scott and Sam Gemar, who were in Johannesburg for the “Made in the USA” Expo, were given a private tour of the excavations and workstations by fellow American Dr Lee Berger, who was recently awarded his doctorate from Wits. Berger, a charismatic and energetic 28 year-old from Savannah, Georgia, has been in South Africa since 1989. In that short period, he has made the headlines with his discoveries at Gladysvale, which lies within a privately-owned game reserve close to Sterkfontein. Berger began excavations at the site in 1991, and has uncovered over 50 000 fossils. At another site near Sterkfontein, called Kromdraai (crooked bend), Broom discovered the first robust type ape-man, Australopethicus robustus, in 1938. This type of hominid has enormous teeth and jaws with huge chewing muscles for processing plant material. Robustus is recognised as belonging to a side branch of human evolution that became extinct about 1 million years ago. Yet another cave in the Sterkfontein area, Swartkrans (black gorge), has yielded not only hundreds of hominid fossils, but also the earliest evidence of the use of fire some 1.5 million years ago. South Africa’s potential for yielding new information about man’s earliest ancestors has been re-emphasised in the past year, with the opening of seven new excavations, and there are close to 100 other known sites waiting to be opened. Tobia and Berger are prime movers behind the fostering of archaeo-tourism. The vision that is being put into practice is one where tours are conducted by well-known scientists who travel to the famous and historic caves near Johannesburg and to more distant sites. Makapansgat, Cave of Hearths, Buffalo Cave, Ficus Cave and Peppercorn Cave all lie amid beautiful bushveld surroundings in the northern Transvaal, near the famous Kruger National Park, where the buffalo – and elephant, lion, cheetah, rhino, and leopard – roam. “Fossils, not gold and diamonds, are South Africa’s crown jewels – the country’s real underground treasure,” says Berger. ‘They don’t represent the history of a single race or culture or civilisation, rather the history of every human being on the planet. The genetic make-up of every person who walks on earth today is in these fossils. “South Africa can take pride in being recognised throughout the world as not only the birthplace of the science of palaeo-anthropology, but also as the place that may be able to claim to be the birthplace of all humankind.”

Anita Allen is the science correspondent of The Star; Johannesburg

South Africa, The Journal of Trade, Industry and Investment

Publisher, David Altman

Writer, Anita Adams